An Introduction to Word Embeddings - Part 1: Applications

If you already have a solid understanding of word embeddings and are well into your data science career, skip ahead to the next part!

Human language is unreasonably effective at describing how we relate to the world. With a few, short words, we can convey many ideas and actions with little ambiguity. Well, mostly.

Because we’re capable of seeing and describing so much complexity, a lot of structure is implicitly encoded into our language. It is no easy task for a computer (or a human, for that matter) to learn natural language, for it entails understanding how we humans observe the world, if not understanding how to observe the world.

For the most part, computers can’t understand natural language. Our programs are still line-by-line instructions telling a computer what to do — they often miss nuance and context. How can you explain sarcasm to a machine?

There’s good news though. There’s been some important breakthroughs in natural language processing (NLP), the domain where researchers try to teach computers human language.

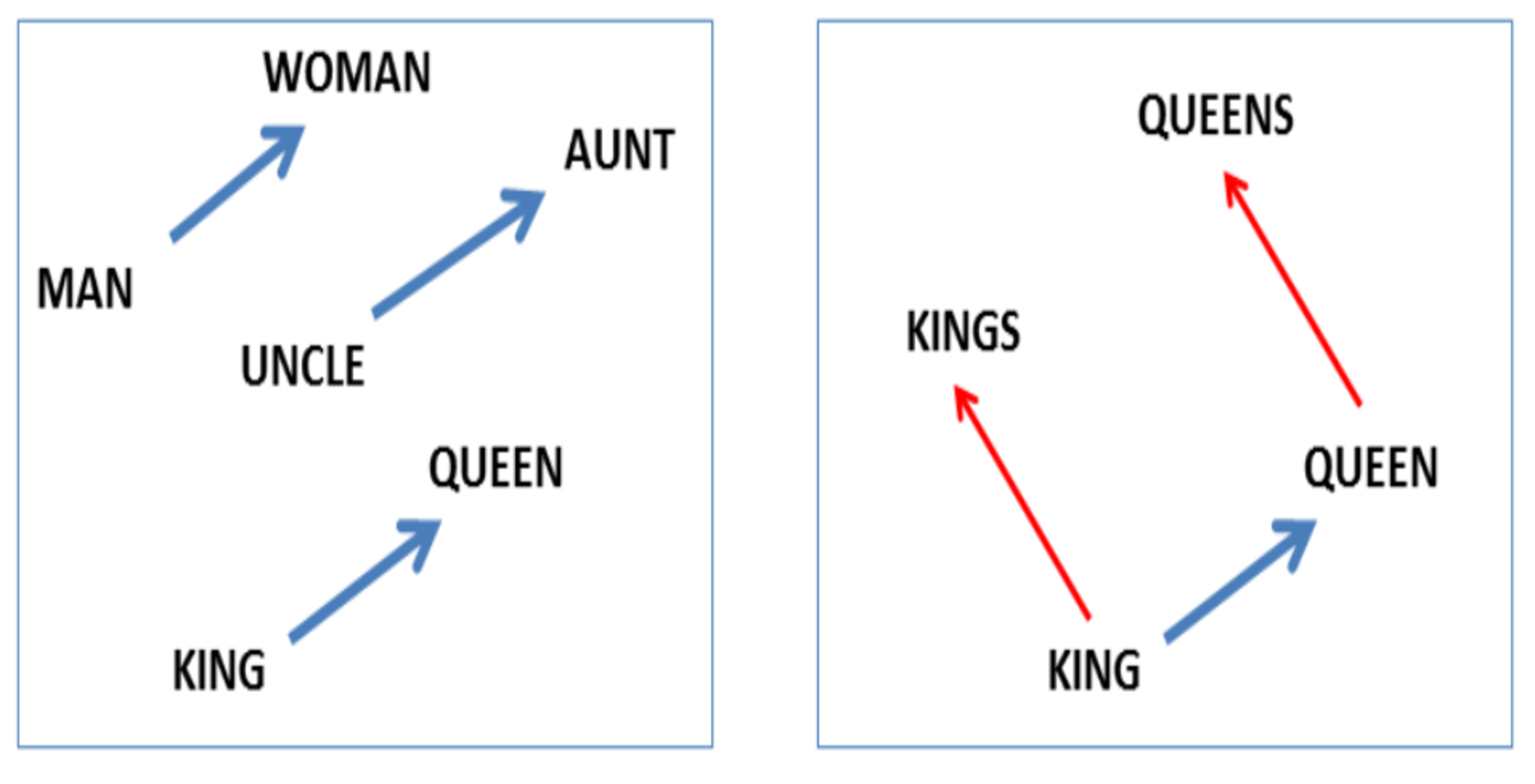

Famously, in 2013 Google researchers (Mikolov 2013) found a method that enabled a computer to learn relations between words such as:

king-man+woman≈queen.

This method, called word embeddings, has a lot of promise; it might even be able to reveal hidden structure in the world we see. Consider one relation it discovered:

president-power≈prime minister

Admittedly, this might be one of those specious relations.

Joking aside, it’s worth studying word embeddings for at least two reasons. First, there are a lot of applications made possible by word embeddings. Second, we can learn from the way researchers approached the problem of deciphering natural language for machines.

In Part 1 of this article series, let’s take a look at the first of these reasons.

Uses of Word Embeddings

There’s no obvious way to usefully compare two words unless we already know what they mean. The goal of word-embedding algorithms is, therefore, to embed words with meaning based on their similarity or relationship with other words.

In practice, words are embedded into a real vector space, which comes with notions of distance and angle. We hope that these notions extend to the embedded words in meaningful ways, quantifying relations or similarity between different words. And empirically, they actually do!

For example, the Google algorithm I mentioned above discovered certain nouns are singular/plural or have gender (Mikolov 2013abc):

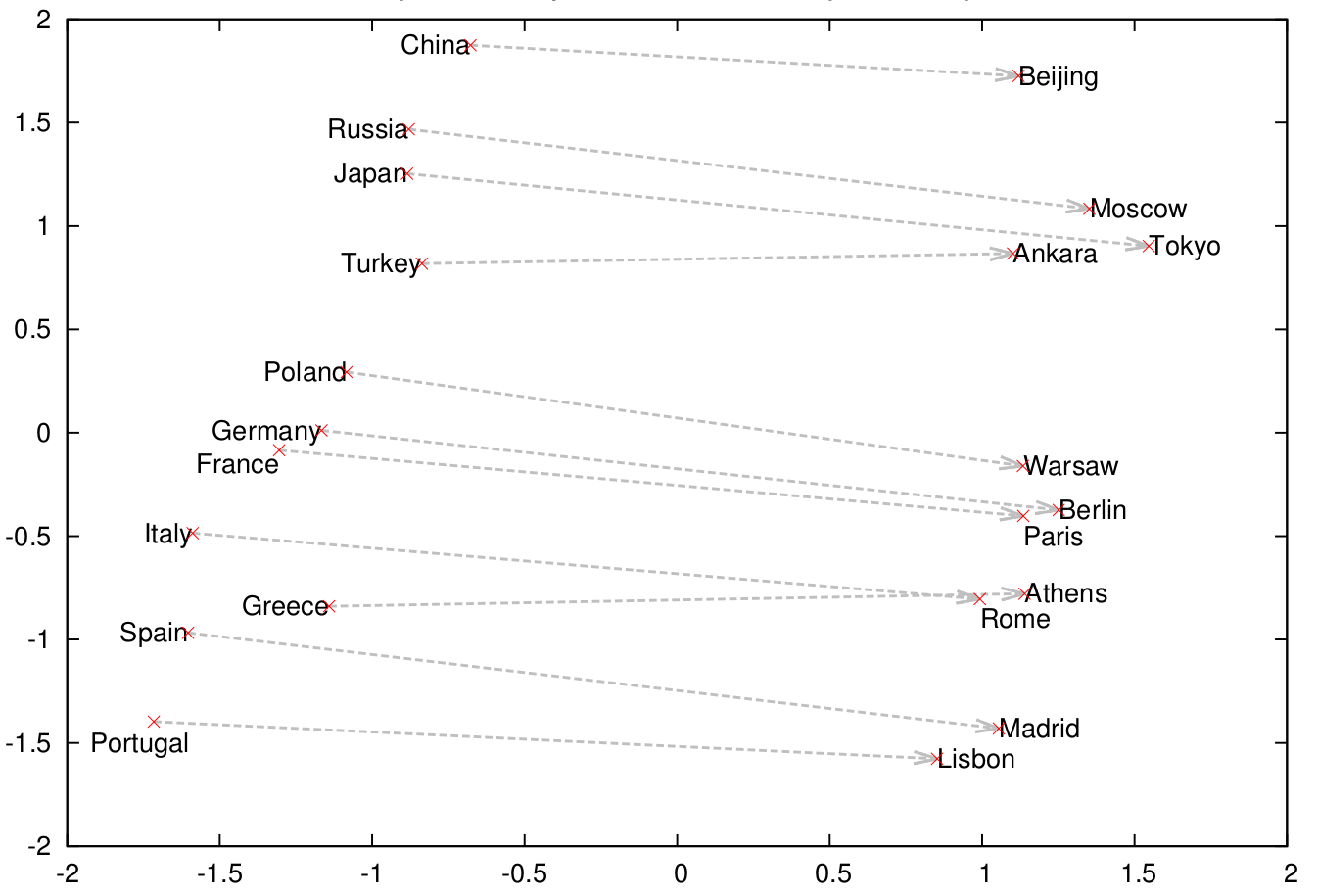

They also found a country-capital relationship:

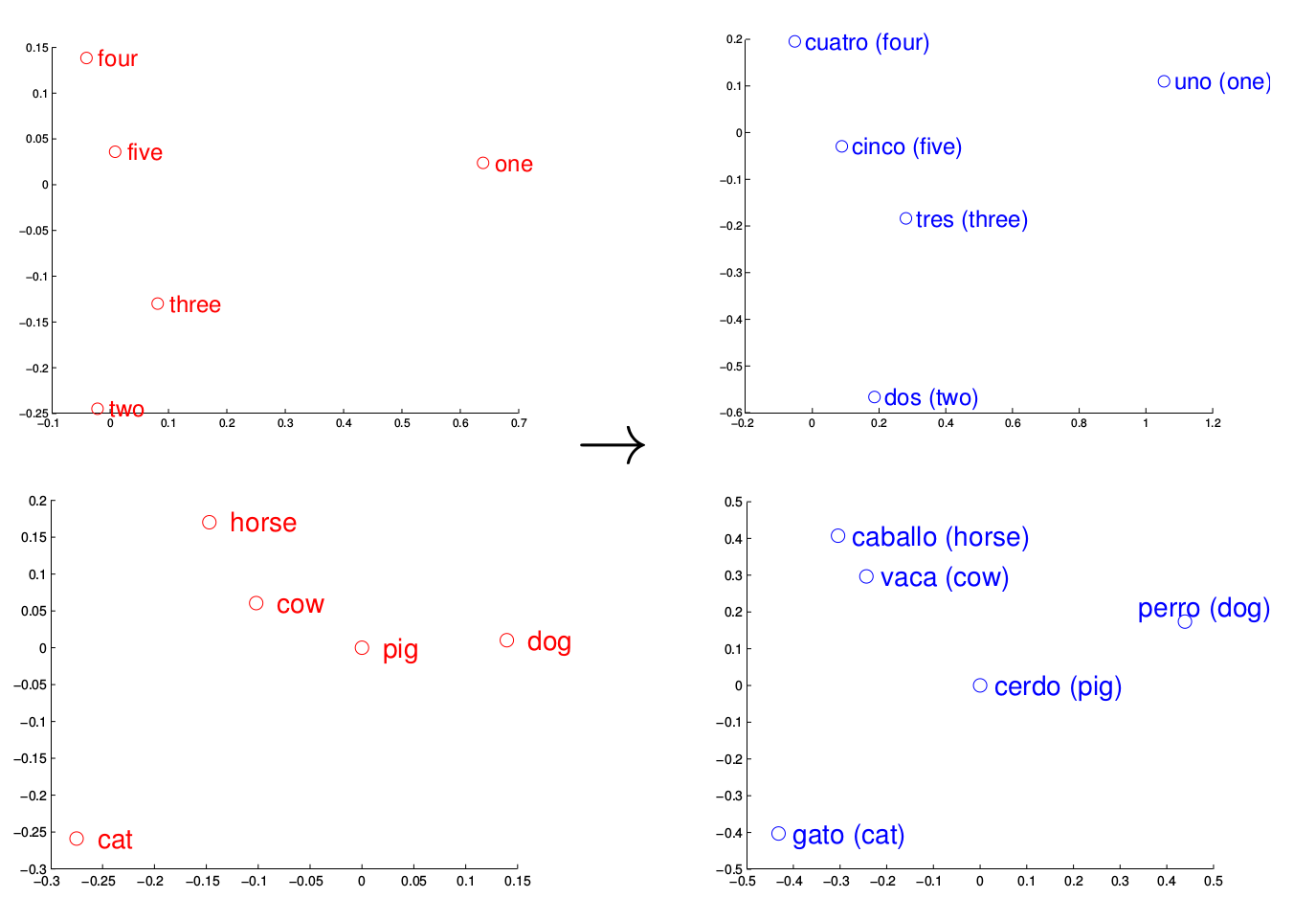

And as further evidence that a word’s meaning can be implied from its relationships with other words, they actually found that the learned structure for one language often correlated to that of another language, perhaps suggesting the possibility for machine translation through word embeddings (Mikolov 2013c):

They released their C code as the word2vec package, and soon after, others adapted the algorithm for more programming languages. Notably, for gensim (Python) and deeplearning4j (Java).

Today, many companies and data scientists have found different ways to incorporate word2vec into their businesses and research. Spotify uses it to help provide music recommendation. Stitch Fix uses it to recommend clothing. Google is thought to use word2vec in RankBrain as part of their search algorithm.

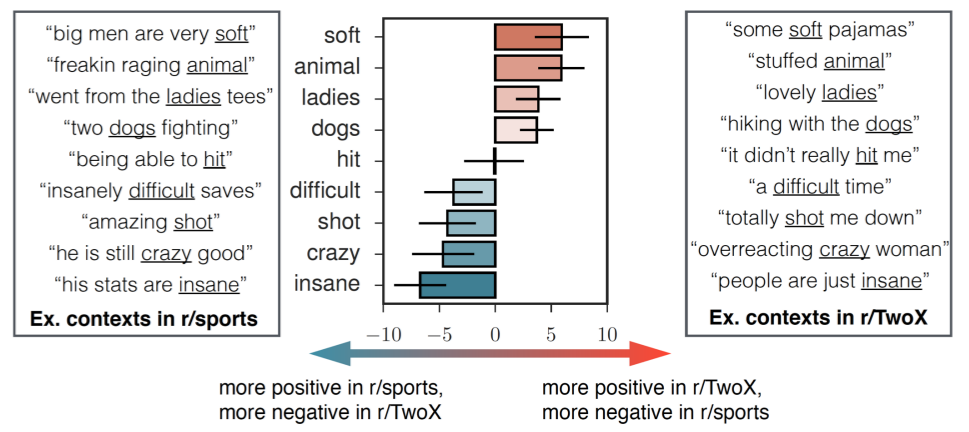

Other researchers are using word2vec for sentiment analysis, which attempts to identify the emotionality behind the words people use to communicate. For example, one Stanford research group looked at how the same words in different Reddit communities take on different connotations. Here’s an example with the word soft:

As you can see, the word “soft” has a negative connotation when you’re talking about sports (you might think of the term “soft players”) while they have a positive connotation when you’re talking about cartoons.

And here are more examples where the computer could analyze the emotional sentiment of the same words across different communities.

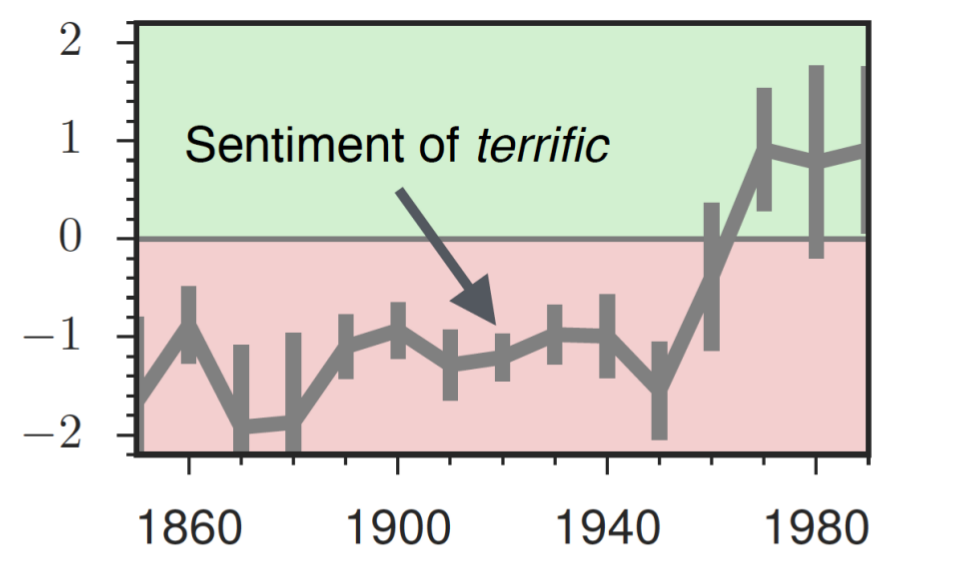

They can even apply the same method over time, following how the word terrific, which meant horrific for the majority of the 20th century, has come to essentially mean great today.

As a light-hearted example, one research group used word2vec to help them determine whether a fact is surprising or not, so that they could automatically generate trivia facts.

The successes of word2vec have also helped spur on other forms of word embedding—WordRank, Stanford’s GloVe, and Facebook’s fastText, to name a few major ones.

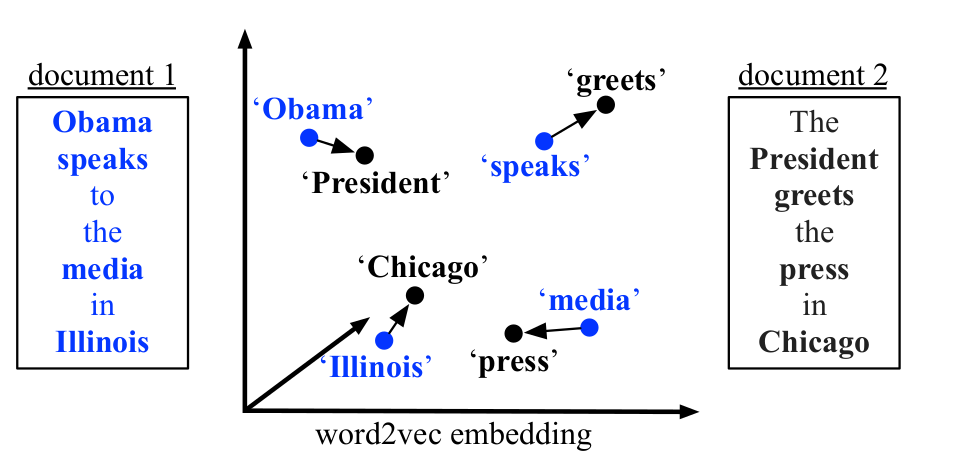

These algorithms seek to improve on word2vec — they also look at texts through different units: characters, subwords, words, phrases, sentences, documents, and perhaps even units of thought. As a result, they allows us to think about not just word similarity, but also sentence similarity and document similarity—like this paper did (Kusner 2015):

Word embeddings transform human language meaningfully into a form conducive to numerical analysis. In doing so, they allow computers to explore the wealth of knowledge encoded implicitly into our own ways of speaking. We’ve barely scratched the surface of that potential.

Any individual programmer or scholar can use these tools and contribute new knowledge. Many areas of research and industry that could benefit from NLP have yet to be explored. Word embeddings and neural language models are powerful techniques. But perhaps the most powerful aspect of machine learning is its collaborative culture. Many, if not most, of the state-of-the-art methods are open-source, along with their accompanying research.

So, it’s there, if we want to take advantage. Now, the main obstacle is just ourselves. And maybe an expensive GPU.

For the theory behind word embeddings, see Part 2.

Reference

- (Hamilton 2016) Hamilton, William L., et al. “Inducing domain-specific sentiment lexicons from unlabeled corpora.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.02820 (2016).

- (Kusner 2015) Kusner, Matt, et al. “From word embeddings to document distances.” International Conference on Machine Learning. 2015.

- (Mikolov 2013a) Mikolov, Tomas, Wen-tau Yih, and Geoffrey Zweig. “Linguistic regularities in continuous space word representations.” hlt-Naacl. Vol. 13. 2013.

- (Mikolov 2013b) Mikolov, Tomas, et al. “Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781 (2013).

- (Mikolov 2013c) Mikolov, Tomas, et al. “Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality.” Advances in neural information processing systems. 2013.

- (Mikolov 2013d) Mikolov, Tomas, Quoc V. Le, and Ilya Sutskever. “Exploiting similarities among languages for machine translation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1309.4168 (2013).

Remark

This blog content is requested by Gautam Tambay and edited by Jun Lu. You can also find this blog at Springboard.